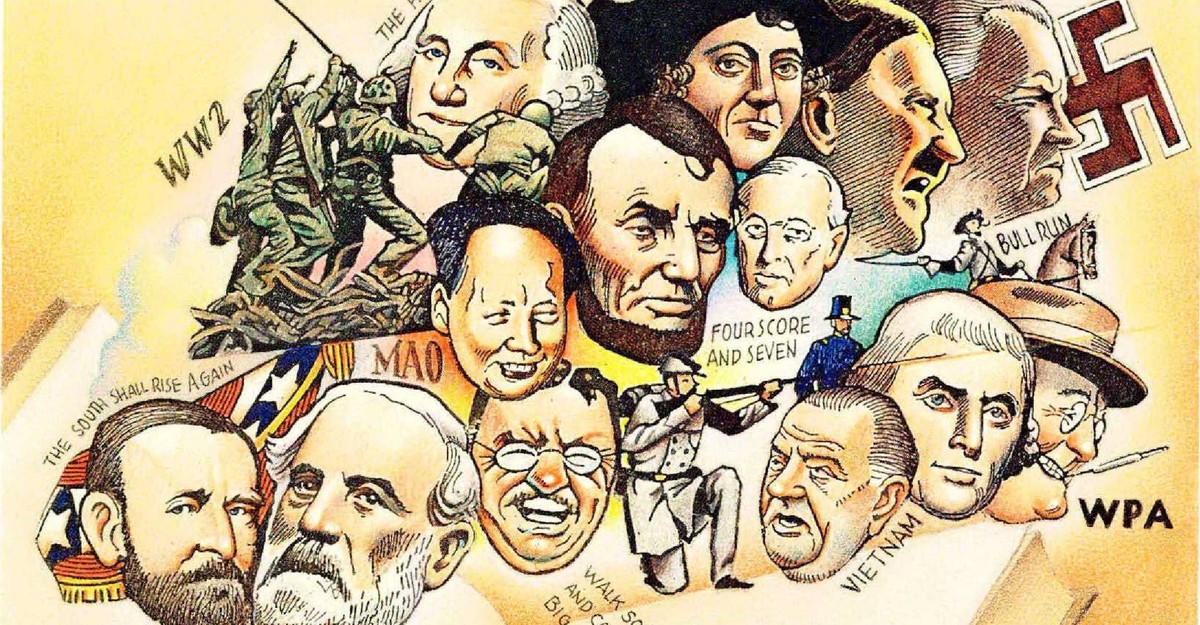

Why We All Need To Study History